B8 - Controlling the temperature of the living environment

Living in houses that are too cold or too hot can contribute to a range of physical illnesses and can cause emotional distress for residents. Exposure to cold temperatures increases the likelihood of developing chest infections and pneumonia, particularly for children and elderly people. If the house is cold and all members of the household sleep in one heated room, these infections can rapidly spread. Extended exposure to high temperatures can also result in illness, with increased risk of dehydration and heat stress for sick children and elderly people.

Survey data show that 24% of 6,000 houses around Australia, on the day of survey, had outside shaded air (ambient) temperatures above 30ºC.

This was an decrease of 9% of houses experiencing similar conditions compared with the 2013 data. Of the houses subjected to these hot conditions, 67% showed some cooling of the inside air temperature (0-2ºC improvement), with only 21% recording an improvement of greater than 10ºC inside. Although this is a significant improvement of 16% since 2013, the ability to cool a house on days exceeding 40ºC can be critical.

Of these the same houses, 81% showed an improvement of air temperature inside the house of 4ºC or greater. In 2013, only 51% of houses improved inside air temperatures by this amount.

These gains, show improvement, but are small when considering that ambient temperatures regularly exceed 40ºC for 62% of the total houses surveyed.

In contrast to the hot conditions above, only 6% of 6,000 houses had outside air temperatures of less than 15ºC at the time of survey.

In these cooler climates, the average improvement in inside temperatures provided by houses was 4.9ºC. This represents a 1.1ºC decrease in improvement of temperatures inside the house, in cool conditions, since 2013.

It can be expensive to use ‘active’ heating and cooling systems, such as heaters and air conditioners to make poorly performing houses more comfortable. ‘Active’ means a heating and cooling system that requires additional energy to make the house warmer or cooler, including gas, fire and electricity. The connection between rising energy costs, poorly designed houses requiring active heating or cooling, the cost of active heating and cooling and poverty are becoming more apparent. Even though Controlling the Temperature of the Living Environment is currently a lower health priority (the 8th priority of the 9 Healthy Living Practices), the link between energy disconnection due to excessive bills for heating and cooling and the loss of all house energy to power the health giving services of a house, as for example, hot water for washing and kitchen appliances, cannot be underestimated.

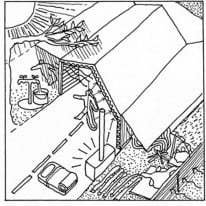

The alternative to an ‘active’ heating or cooling system is a ‘passive’ system, which does not use additional energy. A verandah that shades a wall and reduces heat inside the house is an example of passive cooling and a concrete slab that is warmed by the sun during the day in winter to keep the house warm at night is an example of passive heating. Houses that incorporate passive design features will require less days of active heating and cooling and less energy will be required to heat or cool the house on extreme temperature days. This means reduced costs for the resident.

The Australian data will be distorted, indicating cooling of houses is the predominant problem, by the following:

- the Housing for Health surveys were conducted in the daytime and higher afternoon temperatures are represented whereas colder late night and early morning temperatures, in desert areas, are not.

- more of the 170+ Housing for Health projects represented in the data, have been run in warmer rather than colder climate regions

Regardless of these limitations, this detailed Australian data indicates that these houses provide little benefit to residents in terms of protection from temperature extremes.

This section is not about the fine adjustment of temperature, humidity and airflow to achieve human comfort levels to within a few degrees of 21ºC throughout the year. It is about providing simple, in the first instance passive methods (using no additional external energy) of thermal control to reduce gross temperature extremes that are detrimental to health.

In time it is hoped that the Guide will increasingly represent the health and living environment related issues in in a broader range of climatic conditions such as the arctic region and countries experiencing long cold winter periods.